Regionalism

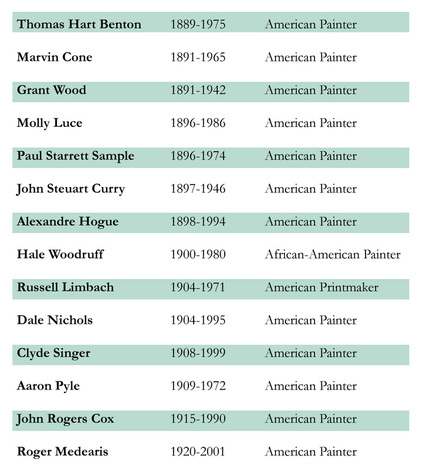

Regionalism was an American art movement that emerged in the Midwest in the early 1930s and continued into the early 1940s. It is often considered a reactionary movement that was a rejection of the European avant-garde of Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp among others—those artists commonly grouped under the “Modernism” label. Concerned with rural subjects and depicting American culture and traditions, Regionalism has been incorrectly denigrated as an American version of fascist art—that it was specifically anti-Modernist in its form, goals, and subject matter. However, the leading artist and promoter of the Regionalist movement, Grant Wood, believed that Regionalism was a type of Modernism. Wood’s perception and the more common one of today are so difficult to reconcile, and the negative view of Regionalism is so ingrained, that it is tempting to simply reject Wood’s views as naïve.

However, “Modernism” was not a clearly-defined idea in American art before World War II, and Regionalism has deep historical roots in American art, continuing a tradition begun with the Hudson River School in the 1860s and extending into the present. Primarily a realist movement, Regionalist artists such as Grant Wood, its leading proponent, and his compatriots Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, drew their subject matter and inspiration from local traditions: the Midwestern farm landscape and the history of their home towns and native region—the Midwest.

However, “Modernism” was not a clearly-defined idea in American art before World War II, and Regionalism has deep historical roots in American art, continuing a tradition begun with the Hudson River School in the 1860s and extending into the present. Primarily a realist movement, Regionalist artists such as Grant Wood, its leading proponent, and his compatriots Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, drew their subject matter and inspiration from local traditions: the Midwestern farm landscape and the history of their home towns and native region—the Midwest.

Essentially a rejection of abstract art and the “foreign” influence of France and Europe, Regionalism sought to create an indigenous, modern American art. The goals of this movement for elevating and establishing an American school of art comparable to the historical schools of Europe are identical to those of the later Abstract Expressionists in New York, but employed very different approaches and means to accomplish this end. Regionalism argued that artists should look to their local history and native concerns rather than modeling themselves and their art on what was happening in Europe.

During the Depression in the 1930s, Regionalism, (also called “American Scene” painting), became the unofficial style of the Work Progress Administration. Most of the art produced in the Midwest under the WPA, and decorating post offices and other Federal buildings, follows the Regionalist approach. This connection is not surprising since this major Federal project followed an earlier one called the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) which ran from 1933-1934. Grant Wood was the head of the Iowa section of the PWAP, choosing and organizing artists to create murals for buildings in Iowa.

Regionalism was part of the debate over “Modernism” in America. This conflict among artists and intellectuals was a conflict over who would decide what this new “American” art would be; by the 1940s this debate had evolved into two “camps” that were divided geographically: the Regionalists, whose work was realist and who primarily lived in rural areas (and were promoted by conservative, Anti-Modernist critics such as Thomas Craven) and the Abstract artists who primarily lived in New York (and were promoted by the Pro-Modernist critics such as Alfred Stieglitz).

But as Abstract Expressionism emerged, the Pro-Modernist critics used their new position of power in the art world as a chance to “settle the score” with the Anti-Modernists. Because Regionalism was on the “wrong side” of the argument, it has been neglected and misrepresented as a result. The difference between the urban, abstract Modernism and the rural, Regionalist Modernism promoted by Wood, Benton, Curry and others is as much a matter of social class and economics as it is an issue of where the artists lived. The abstract Modernists were all living in and around New York and their supporters included some of the richest patrons of American art; the Regionalists were living in the Midwest—Iowa, Kansas and Missouri—and were often patronized by either the Federal WPA programs or by more middle-class locals.

The major social changes of the 1940s after World War II, along with Regionalism’s relationship with the WPA—starting in the 1940s governmental sponsorship of art became very suspect because both fascist, and the communist countries during the cold war, used art as a vehicle for propaganda—meant that the social conditions that promoted Regionalism had changed.

However, Regionalism bridged the gap between a completely abstract art and the academic realist art in much the same way that the Post-Impressionists (Cezanne, Van Gogh, Renoir and Gauguin among others) had done in France a generation earlier. The Regionalists prepared the way for Abstract Expressionists to emerge in America (for example, Jackson Pollock’s drip technique originated with exercises Thomas Hart Benton used in the art classes Pollock took while a student). Regionalism had the same influence on later American art that the Post-Impressionists had in France with the European Modernists.

The Regionalist focus on subject matter—agrarian and largely rural landscapes—has worked against understanding it as the pre-WWII American Modernist movement (the sheer number of artists involved dwarfs the earlier Modernist developments in New York) because its realist subject matter was used by Anti-Modernist critics as proof that abstraction was inherently bad art and un-American. With the rise of abstraction and Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, Regionalism suffered the same loss of art-world status as the conservative critics who promoted it in the 1930s. All these historical factors converged on it with the result that Regionalism has ultimately suffered from a greater misrepresentation and misunderstanding than any other Modernist art, a misrepresentation that continues today.

During the Depression in the 1930s, Regionalism, (also called “American Scene” painting), became the unofficial style of the Work Progress Administration. Most of the art produced in the Midwest under the WPA, and decorating post offices and other Federal buildings, follows the Regionalist approach. This connection is not surprising since this major Federal project followed an earlier one called the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) which ran from 1933-1934. Grant Wood was the head of the Iowa section of the PWAP, choosing and organizing artists to create murals for buildings in Iowa.

Regionalism was part of the debate over “Modernism” in America. This conflict among artists and intellectuals was a conflict over who would decide what this new “American” art would be; by the 1940s this debate had evolved into two “camps” that were divided geographically: the Regionalists, whose work was realist and who primarily lived in rural areas (and were promoted by conservative, Anti-Modernist critics such as Thomas Craven) and the Abstract artists who primarily lived in New York (and were promoted by the Pro-Modernist critics such as Alfred Stieglitz).

But as Abstract Expressionism emerged, the Pro-Modernist critics used their new position of power in the art world as a chance to “settle the score” with the Anti-Modernists. Because Regionalism was on the “wrong side” of the argument, it has been neglected and misrepresented as a result. The difference between the urban, abstract Modernism and the rural, Regionalist Modernism promoted by Wood, Benton, Curry and others is as much a matter of social class and economics as it is an issue of where the artists lived. The abstract Modernists were all living in and around New York and their supporters included some of the richest patrons of American art; the Regionalists were living in the Midwest—Iowa, Kansas and Missouri—and were often patronized by either the Federal WPA programs or by more middle-class locals.

The major social changes of the 1940s after World War II, along with Regionalism’s relationship with the WPA—starting in the 1940s governmental sponsorship of art became very suspect because both fascist, and the communist countries during the cold war, used art as a vehicle for propaganda—meant that the social conditions that promoted Regionalism had changed.

However, Regionalism bridged the gap between a completely abstract art and the academic realist art in much the same way that the Post-Impressionists (Cezanne, Van Gogh, Renoir and Gauguin among others) had done in France a generation earlier. The Regionalists prepared the way for Abstract Expressionists to emerge in America (for example, Jackson Pollock’s drip technique originated with exercises Thomas Hart Benton used in the art classes Pollock took while a student). Regionalism had the same influence on later American art that the Post-Impressionists had in France with the European Modernists.

The Regionalist focus on subject matter—agrarian and largely rural landscapes—has worked against understanding it as the pre-WWII American Modernist movement (the sheer number of artists involved dwarfs the earlier Modernist developments in New York) because its realist subject matter was used by Anti-Modernist critics as proof that abstraction was inherently bad art and un-American. With the rise of abstraction and Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, Regionalism suffered the same loss of art-world status as the conservative critics who promoted it in the 1930s. All these historical factors converged on it with the result that Regionalism has ultimately suffered from a greater misrepresentation and misunderstanding than any other Modernist art, a misrepresentation that continues today.

Information from: http://www.artcyclopedia.com/ and http://www.siouxcityartcenter.org/collections/category/regionalism.html